When it comes to ensuring fire-safety in buildings, fire compartmentation is key. Being able to confine a fire and the resulting toxic smoke and gases for a guaranteed period of time allows people to get out safely, provides safer access for firefighters, and limits the damage done to the building and its contents.

The theory of fire compartmentation is simple and elegant. With this, a building is effectively made up of separate blocks, each of which is fire-resistant. Say there are four compartments, two on the ground floor and two above. If a fire breaks out in the top right-hand compartment, then the fire-resistant walls, floors and ceilings, plus fire doors, will contain the fire within that block and prevent it from spreading throughout the entire building for a period of time. Where things become a little more complex is where those fire-resistant barriers have to be breached.

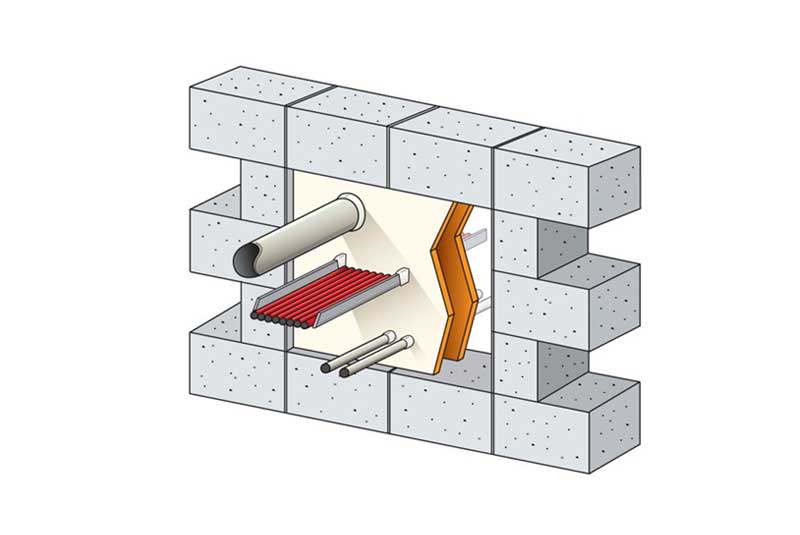

All buildings need services – heating, air conditioning, plumbing, electrics, data cabling and more. Providing those services to the areas where they are needed means that both vertical and horizontal barriers – walls and floors – need to be opened up. When that happens, sealing those openings again becomes crucial to maintaining the integrity of the fire-safety system. Both the conduit and the material used to seal the gaps around it must be capable of resisting the spread of fire and limiting the passage of smoke and gases for the same length of time as the walls and floors.

There are two issues here: making sure appropriate materials are used, and making sure the people who fit them are competent and knowledgeable.

Identifying appropriate materials should be easy. After all, manufacturers are required to state whether their products are fire-resistant and rate them in line with performance. UK Class O rated materials, for example, must prevent surface spread of flame and have a low fire propagation index – in other words, they won’t add to the heat or intensity of a fire.

When it comes to sealing the gaps around a service channel, expanding polyurethane fire-rated foam is a popular medium. On the surface, it’s ideal; it simply fills all the gaps and crevices and hardens to a permanent finish. And if the foam is fire-resistant to the correct standard, that’s fine.

Where things get complicated – and dangerous – is where the foam has been rated against performance in reaction-to-fire tests, which are less stringent than fire-resistance tests.

A further consideration is that even appropriately chosen foams are sometimes used outside of the scope of their tested performance. If testing affirms the fire-rated foam will work when used to fill the gaps around ductwork, for example, but it is then used to fill larger holes in a fire compartment barrier, then it may well fail.

The key message here is, always ensure that the fire test data relates to the intended end use.

If you are using a competent firm of installers, then they ought to understand these issues and take care of this for you. But, our advice is to never assume and ask all contractors to check they understand the requirements. Passive fire protection plays a vital role in protecting lives and property – provided the right materials are installed in the right way by competent people.